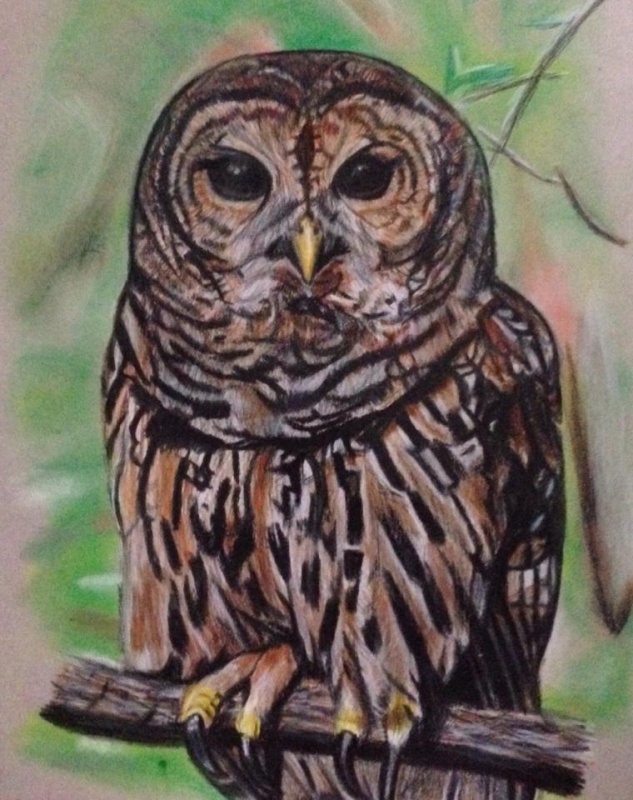

Barred Owls

I don't remember exactly how long it has been since I first caught a glimpse of the Barred Owl flying across a trail in the park where my dog and I walk daily. Over a period of two or three years I encountered it on several occasions, but it was usually no more than a fleeting apparition. One blustery day last February as I trudged along the path into the wind, I spotted the owl perched in a tall pine tree. Both the owl and the tree swayed wildly with each chilly gust. I immediately sat down and watched in fascination as the owl continued its nap while being rocked back and forth by the motion of the tree. Reluctantly I finally moved on, strangely affected by being in the presence of this magnificent creature and wondering if I would be fortunate enough to catch sight of it again.

I returned the following Saturday and eagerly headed up the path, hoping that the owl would still be in the area. It didn't take me long to conclude that any owl who wanted to get a decent day's sleep on a week-end in the middle of a busy Washington D.C. park would have to find a more out-of-the-way perch. I wandered down a side trail that appeared to be much less popular among the steady stream of hikers, joggers, dogs and horses, and began a tree-to-tree search of a grove of pines. Much to my delight, I was rewarded within a few minutes by the remarkable sight of not one, but a pair of barred owls perched side by side directly over the trail. I found myself totally enchanted by these beautiful and stately birds who dozed peacefully, occasionally opening a sleepy eye to peer down at me. I visited this spot again several times in the next few days, and each time they were on the same branch. I sat watching silently as joggers, dog walkers and hikers hurried past without looking up, and I wondered how many times in the past I had done the very same thing.

I was aware that it was courtship season for the owls, and I was curious to see if I could witness a little more activity if I returned later in the day. When my rotating work schedule allowed me a free afternoon, I returned at dusk and sat behind a bush, waiting to see what would happen. Just as the sun was going down, the owls erupted into an ear-splitting cacophony of squawks and hoots, finally flying to separate trees nearby. The female sat on her branch ruffling her feathers and calling loudly until the male flew over and landed on top of her. As I watched them mate - a process that took only a few seconds - I was somewhat amazed that I was being afforded a view of this act of owl intimacy. Long after they flew off into the dark, I continued to sit there, spellbound. I wanted to know more about these intriguing creatures of the night. Would it be possible, I wondered, to discover where they made their nest? And how does one go about locating the nest of such secretive beings? I knew that they would most likely choose a hollow tree, of which there were countless numbers on that trail alone. During the next few days I consulted some of my books and questioned some more experienced birders, all of whom agreed that trying to find a barred owl's nest would be much like trying to find a needle in a haystack. Nonetheless, not being knowledgeable enough to be easily discouraged, I decided to undertake my search.

As I considered how to proceed, I was determined to create as little disturbance in the woods as possible. Fearing that my enthusiasm might interfere with my good intentions, I set out the following ground, rules for myself:

- Go alone. (Although I have been blessed with a dog who is very quiet in the woods, even he would be excluded from my twilight forays.)

- Do not leave the established trails.

- Do not turn on a light.

Now I was ready to begin. I had no idea whether or not owls usually choose a nesting site that is near the place where they roost and mate, but that seemed like the place to start. I was no longer seeing the owls on their usual branch, so I began a systematic search of other trees in the vicinity. My plan was to identify their tree and then sit back and watch. I tried to picture what I thought the nesting tree would look like, but of course the number of trees that fit my mental image made my task daunting. Occasionally on daytime walks I would find a tree that looked like a possibility. I would return at dusk to observe from the bushes, only to hear an owl calling from the opposite direction as if to say, "You've got the wrong tree - try again!".

One night I staked Out an old sycamore with a large opening that clearly had an inhabitant. I was certain I had found my tree. But the gray fuzzy object that I could see in the opening of the tree turned out to be the hind end of a racoon trying to stuff itself into the hole to get out of the rain. It was an amusing sight, and it occurred to me that I must be an equally amusing sight, sitting behind the bushes in the dark beneath my red umbrella.

After several weeks of trekking, rain or shine, through an ever-increasing territory, I realized that I would never be able to guess which one of the hundreds of likely trees actually held the nest. If I was to learn where it was, I would have to find out directly from the owls. My tactics would have to change. Ground rule number 4 was added to my list: select a spot and stay put. I now began choosing a different site each evening and sitting silently until darkness fell. I would make note of the direction from which I heard the owls' first call of the night and then listen for any subsequent calls that came from a different place. Each visit would result in another bit of information that would help me decide where to sit the following night.

By now all of March and the first part of April had passed. I found myself counting the hours each day at work until I could dash off to the park, and the end of daylight savings time was a cause for real celebration. I gradually came to realize that what I was so eagerly anticipating was more than just the search for the owls. The enormous sense of beauty and tranquillity that fell over the forest just before sunset had found its way into my soul as well. Being there alone as the sounds of the day ended and the golden rays of the sun filtered through the towering tulip poplars was a magical experience. By now the wood thrushes had arrived, and I was captivated by their unimaginably pure and sweet song. And I was meeting other woodland inhabitants as well, such as the two small deer who wandered out of the underbrush one night and peeked at me from behind a tree. As they proceeded to browse within a few feet of me, I could hear their gentle chewing sounds, the shuffle of their hooves in the leaves, and the snorts of a nearby adult who didn't share their lack of concern for my presence. The success or failure of my mission was becoming less important than the way in which I was becoming connected to this special place.

I discovered that I had developed a sense of protectiveness that surprised me in its intensity. Tears came to my eyes when I saw shrieking children dashing through the woods, trampling everything in their path, or dogs crashing through the underbrush in pursuit of deer. I thought of the owls watching from above and felt ashamed of the lack of respect being shown for them and their home by my species. There were few passers-by who noticed me, and though I told no one what I was doing there, most assumed from my binoculars that I was a bird-watcher. Once in awhile someone stopped to apologize for frightening the birds away, and I would suggest that perhaps their apology should go the birds rather than to me. This led to a number of lively and thoughtful discussions about the impact of our presence on this park that we all treasure. (It also led to some new friendships.)

And meanwhile, much to my amazement, I was actually managing to narrow down the area in which I was searching for the nest. The calls of the owls did not always come from exactly the same place, but a pattern was emerging, even though it had been quite awhile since I had had any actual owl sightings. It crossed my mind that if I was unable to identify the nesting tree before the foliage became thick, my chances of observing anything at all would be slim. I continued the painstaking process of shifting my location just a little each evening based on the owls' calls - another night, another clue. And there were other hints as well, such as the small pile of blue feathers that I noticed several times under the same tree. One evening I didn't hear the owls and was waiting to see what else might happen by that would be of interest. All of a sudden I saw a shadow overhead and looked up to see one of the owls perched right over me, gazing at me intently. We stared at each other until it sailed off as silently as it had come. The next night the owl and I again arrived around the same time, and although I had changed my location slightly, it was quickly able to detect me. It wasn't: long before both owls began appearing regularly in that same vicinity just before dusk.

I was thrilled to see them again, and assumed that their eggs must have already hatched. In spite of my attempts to conceal myself, the owls were always aware of my presence. Each night as I arrived to choose my observation site, I would hear the soft hoots of the female as soon as I entered the area. Several times I saw the male bring a mouse to her, and they would flutter nervously from tree to tree. It was finally beginning to dawn on me that I must in fact be close to finding the nest! I was both ecstatic and incredulous.

One evening I moved to the opposite side of the trail, and the female gave a series of three sharp warning calls. I realized to my dismay that the young owls must surely be inside a tree quite nearby, but would not be fed as long as their parents could see me. There appeared to be few spots from which I would not be visible to the owls from their lofty perches. I resolved that unless I could find a way to observe without disrupting the owl's feeding activity, I would have to end my visits. I surveyed the area anxiously, wondering if I would really be capable of staying away, but not wanting to cause a hungry owlet to miss its meal.

To my relief, I finally came across a space beneath some overhanging vines which would shield me from being seen from above while at the same time giving me a good view of the immediate area. I had been keeping an eye on a tree which appeared to have a large opening in it and sat facing in that direction. Suddenly I heard a twig snap behind me. I turned just in time to see an owl flying from the crotch of a tall tulip poplar, the very tree, in fact, that I had been sitting beneath only the night before. There was a well-concealed opening in the tree that was difficult to see from below, and a slender shoot that was growing just at the entrance was still vibrating. I saw no other activity that night, and I wondered if perhaps my imagination was playing tricks on me.

I literally raced home from work the next night and tiptoed quietly down the trail to my hideaway in the vines. A short time later an owl glided silently into the opening in the tree! I heard the slight "twang" of the small branch as she entered, and again as she left. I had long before accepted the fact that my chances of finding the nest were negligible but had been content to enjoy my other nocturnal adventures. Now I was truly astonished. I found myself chuckling over the possibility of becoming an "owl godmother" and was eager to rush home and tell all my friends of my exciting discovery. But I had experienced first-hand how these owls, who were masters of secrecy, had miraculously developed the ability to live amid every imaginable type of human disturbance. I felt immense respect and admiration for the tireless way in which they worked to protect their young, and I knew I could not betray them. This would be a real lesson in self-discipline.

I excitedly returned following day and heard a great commotion ahead of me on the trail. I crept nearer and saw the male owl sitting in a tangle of vines while a red-tailed hawk perched right over him, screeching into his face. At the same time a dozen crows were dive-bombing him from all directions. The vines were just at my eye-level, and as I peered into the owl's face I whispered, "Yes, I see how much harassment you already have to endure, and your secret is safe with me".

I came back later on to observe the nesting tree, but was determined not to stay too long. On each subsequent evening I returned to check for any sign of a little one. It seemed that although the owls were aware of me when I entered my hiding place, they would forget about me after about fifteen minutes if I remained perfectly still. The old adage "out of sight, out of mind", apparently applies to barred owls. Nine days later I was just about to leave the park when I decided to walk past the tree where the nest was once again. The tree was backlit by the setting sun, and all was quiet. I studied the scene, looking for the adult owls. I turned back around, and as if by magic, there it was - a single wide-eyed, fuzzy baby owl who was literally glowing in the fading rays of the sun. It was for me a moment of pure joy. I dropped to the ground and held my breath, fearing that the owlet would somehow vanish. As it glanced in my direction and blinked its eyes, I said softly, "Welcome to the world. I've been looking for you for a long time."

It had been ten weeks to the day since I had seen the adults mating. I sat watching the baby until there was no longer enough light left for me to make out its fluffy profile, and as I stood up to leave, I heard the sharp calls of the mother. I wandered home with my head in the clouds, my mind filled with the wonderful vision of the little owl.

As hurried back in the morning, I could hear a tremendous uproar as soon as I started down the trail. The crows were audible from nearly a quarter of a mile away. When I arrived at the tree, I spotted the baby in the foliage, a little further up than the night before. High in the trees on either side of the trail the adult owls sat stoically, acting as decoys and willing to endure the taunts of the crows to safeguard their new offspring. I stayed only a few minutes, but returned the following day to find that the baby had moved to the next tree over. Once again the mother hooted her warning. On what was to be my final opportunity to view the little one, it had moved several more yards back into the woods. By the time of my next visit, it was no longer visible. I was, however, able to determine its general location each day in the thick vines and leaves by playing a sort of game of "Mother May I?" with the female. I would start slowly up the trail and she would eventually begin her cooing sounds. I would take a step in each direction, and when I moved toward the place where the baby was concealed, she would launch into her warning calls. I could usually spot her in her vantage point high above me, and I would move on.

I'll confess to being somewhat disappointed that the owlet had moved out of sight so quickly, but merely being aware of its presence nearby was enough to send my spirits soaring. And I was relieved that it was no longer on its perch near the trail where it had been so visible and vulnerable. May had nearly ended when the day finally came that I could no longer find any sign of the mother or the baby. Dusk was approaching, and I decided to take a last walk from the nesting tree back to the mating tree, (a distance of about a quarter of a mile, as it had turned out) reflecting on all that I had experienced in the past few months.

I sat for awhile to listen as the music of the night set in. There was very little daylight left when I became aware of some movement nearby. I sat motionless and watched as an elegant red fox trotted right past me. I laughed silently, supposing that the woodland spirits were reminding me that there was much more to discover here. Of course I returned the next morning and began looking around for the fox's den, which was considerably easier to find than the owls' nest had been. The kits had long-since left home, but I stood for awhile marvelling at the foxes' impressive feat of engineering and looking forward to my next adventure.

During the rest of the summer I would occasionally hear the owls call, but never saw them. One night I decided to stay until dark to see if I could determine what was making some large and unfamiliar tracks that I had seen repeatedly but had been unable to identify. Although I was sitting quietly, I was unaware of the owl that had landed behind me until it began serenading me with a lengthy rendition of every call in its vocabulary. I felt like I had been greeted by an old friend. I was filled with gratitude for this wonderful bird and its mate who had entered my life and forever changed my view of the world.

These days I never pass the Owl Tree without pausing for just a moment to lift my arms in thanks. Learning to approach nature silently and respectfully, with open eyes and an open heart, has been a priceless gift indeed. I know that I've only just begun to discover the wonders that lie right in my own back yard. There are still times when I find myself casting a longing eye at ads for exotic-sounding and (for me) unaffordable nature tours. That's when I realize that there is not a single trip for which I would exchange even a minute of my unforgettable journey with the owls.